Fuzzing WebSockets for Server-Side Vulnerabilities

Table of content

Introduction

TL;DR: If you're only interested in how to use the tool, you can skip directly to the Usage and Automation section.

Since RFC 6455 [1] landed in 2011, WebSockets have become a core part of many real-time applications.

But here’s a paradox: in theory, traditional HTTP vulnerabilities are expected to apply to WebSockets [2][3][4][5][6]. Yet in practice, public reports and CVEs show near-zero WebSocket-specific server-side flaws. This raises the question: are systems truly secure, or is the tooling for WebSocket security still underdeveloped?

This work aims to address that gap by proposing a new approach on how to fuzz WebSocket messages, and also move past the manual analysis required by most existing tools. To achieve this, the Backslash Powered Scanner extension for Burp Suite was enhanced to support WebSocket fuzzing.

In short, our approach allows sending prerequisite messages (e.g. for Socket.IO protocol negotiation) and capturing all resulting messages within a configurable window, enabling correlation between sent and received messages for effective analysis.

You can find it on GitHub.

Brief Explanation of the WebSocket Protocol

This article will not provide a detailed walkthrough of the WebSocket protocol. If you need that level of depth, please refer to RFC 6455 [1].

HTTP is inherently a request-response protocol. The client sends a request, the server replies, and that cycle repeats. This design makes it easy for security tools to insert payloads, observe responses, and flag anomalies. WebSockets, on the other hand, depart entirely from this paradigm.

After an initial HTTP handshake, the connection is upgraded to a persistent, bidirectional channel. From that point on, both client and server can send data independently, at any time, without waiting for a response or following a strict sequence. This results in a communication model that is asynchronous, stateful and long-lived.

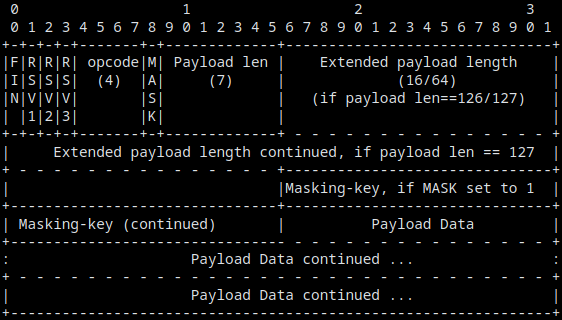

Messages in WebSocket connection are transmitted as frames, which are low-level units that encapsulate the actual payload. Each frame includes metadata such as an opcode (indicating message type), masking information (required for client-to-server messages to mitigate attacks such as cache poisoning), and fragmentation flags (to support message splitting across multiple frames). Each message can be composed of one or more frames, and messages can be of two different types: text or binary. Both types can be intermixed within the same session.

Text representation of a WebSocket frame [1]

There are no HTTP status codes, no headers and no request-response boundaries. Just a stream of raw frames - text or binary, sometimes wrapped in custom formats or encodings - moving in both directions.

This design is great for performance and interactivity, but it's a nightmare for security tools. The assumption that an input will produce a corresponding, immediate response no longer holds. A message might trigger an effect ten seconds later. It might not trigger anything at all, or it might depend on a prior state set earlier in the session. R. Koch also mentions this in his work:

"With WebSockets vulnerability detection is not as easy as with HTTP. When you send a HTTP request there is always a response, where you can easily detect changed output, or slow response times. With WebSockets, communication is bi-directional and asynchronous. There is no request/response pattern, although a sub-protocol in use may define such. As a result automated detection is fairly hard and has to be done manually. However, tools can aid the search for vulnerabilities. The approach to take is similar to stored XSS attacks, where there is often no indication of a vulnerability. While the attack payload is stored in a database, it may appear on any page of the website. If there exists a request-response pattern in the WebSocket communication, you can measure the response time after sending crafted requests. Like with Blind SQL-injection attacks, one could send values that delay the execution of database or file system queries. If the execution slowed down, a hidden vulnerability may be detected." [6]

As a consequence, existing tools and logic mostly built for HTTP traffic are inneffective when applied to WebSocket-based applications.

Brief Discussion of WebSocket Security Tools

While not many, some attempts have been made over the years to improve WebSocket security tooling. Other valuable work exists as well, but here I’ll focus specifically on fuzzers.

The first mainstream tool to support WebSocket testing was Zed Attack Proxy (ZAP). R. Koch’s work [6] was foundational, allowing inspection, message tampering, and a basic fuzzer using a custom wordlist. It was a great start, but it lacked the features needed to handle more complex, layered protocols like Socket.IO, that require specific handshake sequences to even get the conversation started. And, like many tools that followed, the results had to be manually analyzed.

A. Riancho [7] and A. Hauser [8] released similar, lightweight fuzzers. They introduced a key feature: support for "pre-messages" to be sent before the actual payload. This was a step in the right direction for stateful communication. However, they mainly target simple JSON-based applications. While you can adapt them for other formats or multi-step handshakes with custom scripting, it makes them clunky and less effective for protocols like Socket.IO out-of-the-box. Hauser’s tool requires manual inspection via a proxy, while Riancho's includes a limited attempt at automated analysis.

In 2019, M. Fowl [5] proposed a clever but ultimately limited approach: a fuzzing harness that translates WebSocket messages into HTTP requests and back again. This technique allows traditional web application security tools, such as SQLMap, to be used directly for WebSocket-heavy applications. Nevertheless, the approach is limited by its dependence on HTTP translation, which may fail for WebSocket interactions without direct HTTP equivalents. For something like Socket.IO, with its specific handshake and session management messages, this approach simply doesn't work. VDA Labs followed a similar idea with their own prototype [9].

Wsrepl [10], developed by Doyensec, offered a more interactive and exploratory tool rather than a traditional fuzzer. It featured a command-line REPL for sending and receiving WebSocket messages, along with interesting additional utilities such as displaying message opcodes and injecting fake ping messages.

More recently, SocketSleuth [3], by E. Ward, became the first dedicated Burp Suite extension for WebSocket testing, addressing the lack of Intruder-like features. It cleverly bypasses handshake complexities by letting you reuse an existing connection from your browser. This sounds great for Socket.IO, but, connections can be unstable and drop mid-fuzz. Even when a payload is successfully delivered, retrieving it often requires manually sifting through the message history.

Around the same time, PortSwigger released WebSocket Turbo Intruder [11], another Burp extension that uses customizable Python scripts for fuzzing. This makes it one of the most flexible tools available. You can write a script to handle the Socket.IO handshake perfectly. However, this makes the tester responsible for implementing the protocol logic and then manually sift through the results to find vulnerabilities.

A common theme emerges. The lack of automated response analysis is a huge bottleneck, forcing manual review of results. But an even more fundamental challenge is handling the communication itself. Before even thinking about analyzing responses for vulnerabilities in an application using Socket.IO, it is essential to first establish methods for detecting and handling WebSocket messages correctly.

How To Handle WebSocket Messages

As stated, WebSockets are complicated to fuzz. Their asynchronous, stateful nature breaks the usual assumptions that security tools rely on.

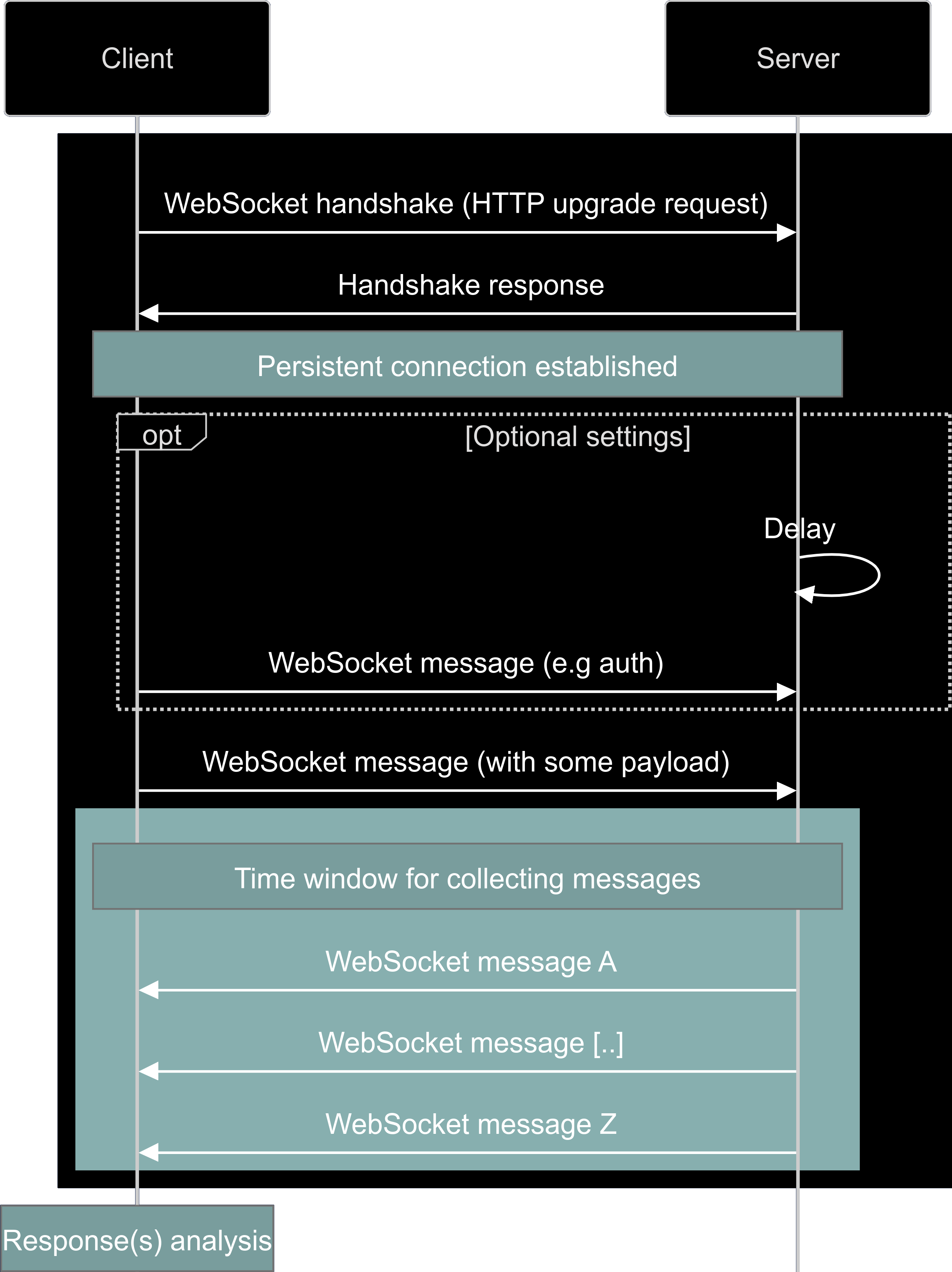

To work around these challenges, this approach focuses on reliability and clarity. A new WebSocket connection is opened for each payload (to avoid side effects from earlier payloads that might affect the application’s state). If necessary (for example, with Socket.IO protocol negotiation), the scanner can wait for a timeout and/or send prerequisite messages before injecting the actual payload. Once the payload is sent, all incoming messages are captured during a configurable time window.

Responses are stored in a structured format, including metadata such as message type (text or binary) and response time. This structured approach enables message correlation and enables more accurate behavioral analysis.

The following visual representation may offer a clearer view:

WebSocket fuzzing flow

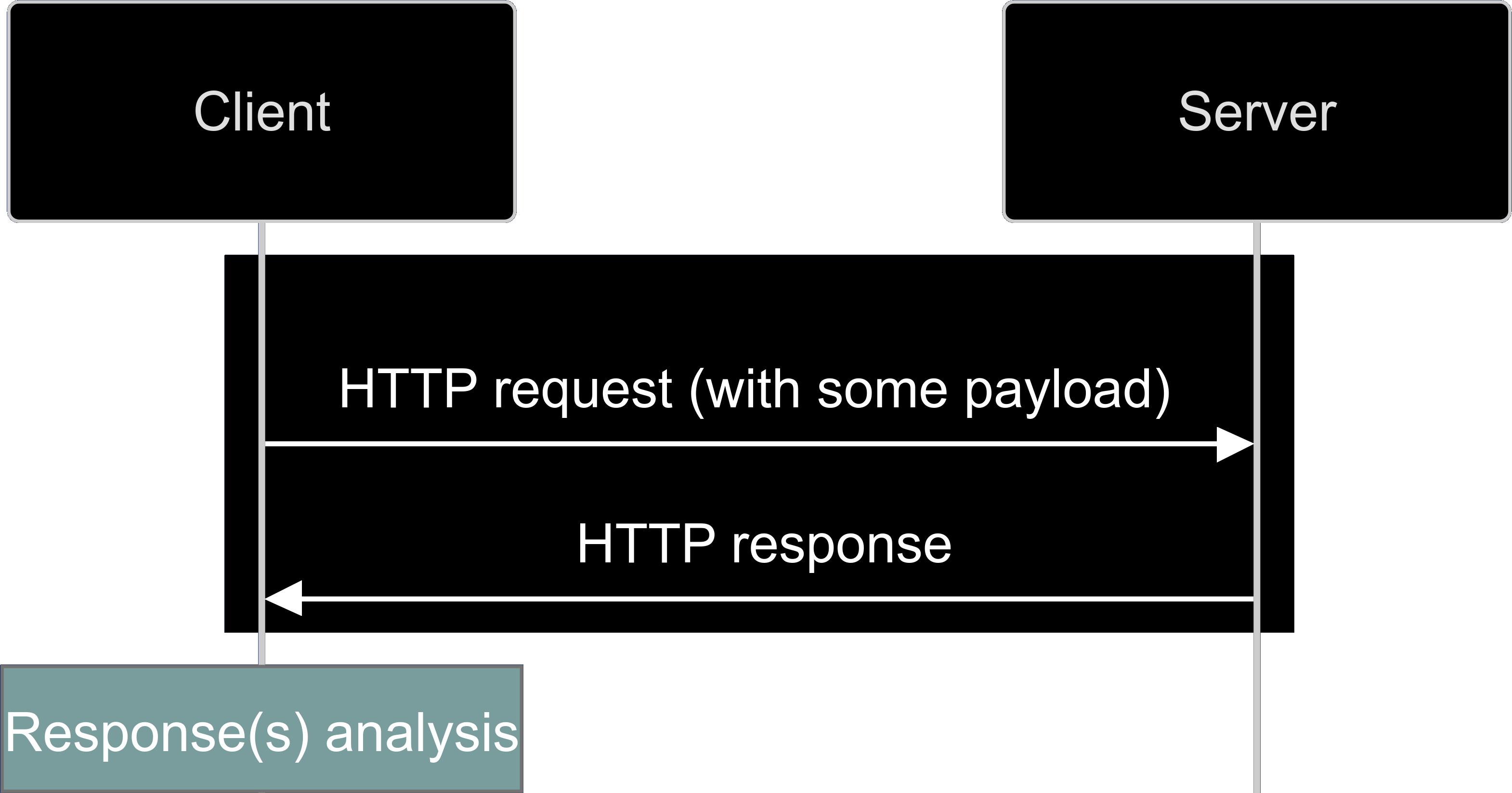

And for comparison, here is the same representation for HTTP, which highlights the added complexity involved in fuzzing WebSocket traffic:

HTTP fuzzing flow

Adding WebSocket support to Backslash Powered Scanner

Brief Explanation of the Backslash Powered Scanner

This article will not provide a detailed walkthrough of the Backslash Powered Scanner extension. If you need that level of depth, please refer to the whitepaper [12].

The Backslash Powered Scanner [12] is a Burp Suite extension that distinguishes itself from traditional vulnerability scanners by adopting an iterative, behavior-based approach inspired by manual testing techniques.

Unlike traditional scanners that rely on predefined, technology-specific payloads, this scanner utilizes a set of generic payloads containing special characters (e.g. backslashes, quotes, braces) to assess how the server processes and responds to these inputs. It begins by modifying the input and evaluating the response against predefined metrics, such as HTTP status codes, the total number of new lines in the response, and the frequency of various keywords. If a deviation is detected, the scanner investigates further; otherwise, the input is disregarded. In essence, rather than explicitly searching for known vulnerabilities, the scanner focuses on identifying anomalous or unexpected behavior, which may indicate potential security flaws.

It has demonstrated considerable effectiveness in fuzzing traditional HTTP-based applications. As such, enhancing it to support WebSocket fuzzing could significantly expand its utility.

Response Analysis

As stated, the Backslash Powered Scanner extension takes advantage of predefined metrics to compare responses. But metrics used for HTTP traffic cannot be directly applied to WebSockets due to the fundamental differences between the protocols. As such, as a starting point, and with the flexibility to expand or refine these metrics in the future, I chose the following:

- the total number of messages received.

- the sequence of received message types (text or binary)

- the individual lengths of received messages

- the number of spaces in each message

- the number of HTML tags in each message

This ensures that WebSocket responses are evaluated based on meaningful attributes rather than traditional HTTP metrics like status codes and headers.

Usage and Automation

Since Burp's Montoya API is still not as mature for WebSocket traffic as it is for HTTP, it's not yet straightforward to automatically fuzz all fields within a message. That said, some automation was manually implemented and can be expanded in the future. For now, and somewhat as a workaround, usage works as follows:

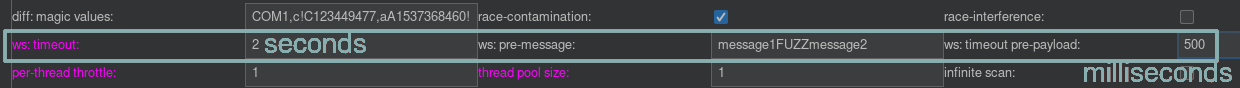

- Configure the settings as needed.

- For simple cases (e.g., sending a message and expecting a single reply), you may only need to set the response capture time window.

- For more complex scenarios (e.g., applications using Socket.IO), you may need to send prerequisite messages such as a

40to complete the protocol handshake, and add a short delay to avoid breaking the connection.

- Select a WebSocket message and launch the extension.

- If the message is in JSON or Socket.IO format, the extension will automatically fuzz all fields and JSON escape the payloads.

- If it's not, you can wrap the desired insertion point with

FUZZ, and the extension will target that area. - If no marker is provided, the extension will fuzz the entire message as a single unit.

In the settings, the response capture time window and, if needed, the delay, should be in milliseconds. If multiple prerequisite messages are needed, they can be separated using the FUZZ string.

Settings example

Future Work and Challenges

There are several areas for improvement. Unfortunately, due to the inherent complexity of WebSockets, it would be impossible to implement everything and take all scenarios into account in the initial release. I chose to build a solid foundation first, with plans for updates over time. That said, here are a few key points to consider:

- Allow the user to open connections directly from a

ws://orwss://URL, in addition to the current method of using the upgrade request. - Allow the user to reuse the same connection, in addition to the current method of creating of creating a new connection for each payload.

- Improve the response analysis metrics.

- Add lower-level metrics (e.g., opcodes) when Burp’s Montoya API supports it.

- Add support for binary messages in some capacity.

- Improved JSON parsing, particularly for array handling

In the real world, WebSockets are chaotic. For example, some implementations send messages to the server in JSON, and the server replies with compressed binary messages. Others require each message to include a timestamp and a signature. Supporting all these scenarios is no small task.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank James Kettle for his openness, his feedback, and for taking the time to answer my questions throughout the process. I am also grateful for the opportunity to contribute to his work.

I would also like to thank Andreas Happe and Erik Elbieh for their availability to answer my questions.

References

Fette, I., & Melnikov, A. The WebSocket Protocol (RFC 6455). IETF. 2011

PortSwigger. Testing for WebSockets security vulnerabilities. Web Security Academy. 2024

Ward, E. Realtime Communications, Realtime Risks. 44CON Information Security Conference. 2023

Shekyan, S., & Toukharian, V. Hacking with WebSockets. Black Hat USA. 2012

Fowl, M., Defoe, N. Stable 35 Old Tools New Tricks Hacking WebSockets. Derbycon. 2019

Koch, R. On WebSockets in Penetration Testing. Technische Universität Wien. 2013

Riancho, A. Websocket Fuzzer. 2018

Hauser, A. WebSocket Fuzzing - Development of a Fuzzer. SCIP. 2023

VDA Labs. Hacking Web Sockets: All Web Pentest Tools Welcomed. 2024

Konstantinov, A. Streamlining Websocket Pentesting with wsrepl. 2023

PortSwigger. WebSocket Turbo Intruder. 2023

Kettle, J. Backslash Powered Scanning: hunting unknown vulnerability classes. PortSwigger. 2016